Press CHIP STRATEGIC AUTONOMY IN QUESTION

Semiconductor supply shortages have intensified the debate on the need to increase European production, in order to ensure greater self-sufficiency. While the European Commission has been working to give the industry a boost, some experts say it may be too little too late.

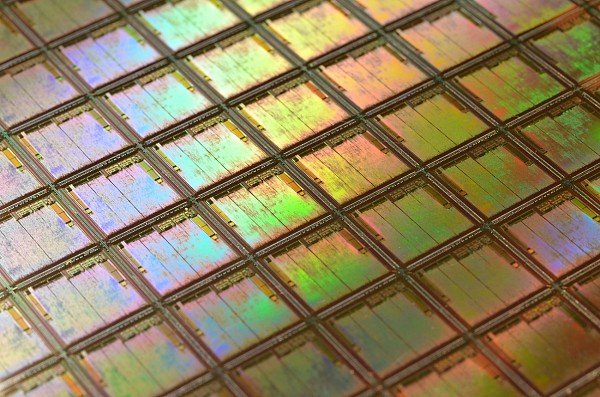

The world is becoming increasingly digital – and everything digital runs on semiconductors. Many sectors, from automotive to healthcare, depend on these tiny chips, which are therefore essential for European industry.

The manufacturing of these semiconductors is characterised by complex production networks. While chips are designed in the US, the EU and elsewhere, their manufacture is outsourced to a handful of foundries, the vast majority of which are located in Asia: Taiwan’s TSMC has more than 50 percent of the global market.

Europe’s lack of manufacturing capacity makes it highly vulnerable to shortages. And that’s what’s happening now: a chip shortage is affecting supply chains around the world, slowing down production of everything from smartphones to household appliances to driver assistance systems. It has severe consequences for many of the EU’s flagship industries, such as car manufacturing. Major carmakers have already announced significant rollbacks in their production, lowering expected revenue for 2021 by billions of dollars.

Bringing production back home

This is a problem the bloc is well aware of. The EU wants to double its share of global next-generation semiconductor production from 10 percent to 20 percent of global volume by 2030. It sees this as essential to achieving the strategic autonomy that leaders keep talking about – and has earmarked 20% of the €672.5 billion stimulus fund for technology investments.

At a meeting with EU telecoms ministers earlier in June, Thierry Breton, internal market commissioner, said Europe has everything to succeed in the race to design and produce semiconductors.

“Europe is today too much dependent on third countries’ supply for the most advanced processors. Europe has everything it takes to position itself at the forefront of the global and technological race.”

At the same ministerial meeting, member states have decided to join forces for a European initiative on processors and semiconductor technologies. To date, 22 EU member states have signed a joint letter, agreeing to work together in order to “bolster Europe’s electronics and embedded systems value chain” and calling to strengthen Europe’s electronics manufacturing capacity.

A need for a market

Maria da Graça Carvalho, member of the European Parliament’s industry committee, defends the need to support this industrial sector.

LISTEN TO MEP MARIA DA GRAÇA CARVALHO DECLARATIONS

“Europe needs to reclaim its manufacturing capability in many sectors. This is crucial for our strategic autonomy because, presently, there is an excessive external dependence. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, this condition even paralysed certain industrial activities, due to the lack of key components. Semiconductors and microprocessors are two examples of key components that we need to be able to produce within our borders.”

However, some believe that it is too late for Europe to jump on the semiconductor bandwagon. It will not be possible to catch up in a sector already dominated by stronger and more experienced competitors. Moreover, the EU needs to rebuild its entire industrial fabric to create sufficient demand.

When asked whether the key to the EU’s strategic autonomy is to increase semiconductor production, Giles Merritt, founder of the Friends of Europe think tank, does not hesitate. The answer is no – and the EU should instead put its money into more relevant investments.

“The short answer is ‘no’. The Commission’s approach is ridiculous. The longer answer is that we have missed the bus on semiconductors. We, Europeans, are never going to get back to where the Taiwanese, the Chinese, the Americans and the South Koreans are.

Europe lagging behind

While Maria da Graça Carvalho believes in the potential of the European semiconductor market, the MEP is concerned about what she sees as the European Commission’s insufficiently ambitious policy in this area.

LISTEN TO MEP MARIA DA GRAÇA CARVALHO DECLARATIONS

Carvalho admits that on developing technological capabilities, the EU is lagging behind, but there is hope.

“The European Union has high ambitions in Digital. It has a partnership, under Horizon Europe, aimed at creating the best network of supercomputers in the World. However, we also need to build an ecosystem that will allow us to benefit fully from our new data processing capabilities.The European Commission, as well as the other European institutions, did not do enough to meet this goal in the past. Otherwise, we would not be speaking about the excessive weight of external suppliers. Nevertheless, I believe that we are much more conscious of this now than we were in the path.”

Merritt disagrees. Not only does he argue that the European Union should focus on developing new, different technologies in the areas where research and innovation have proved to be more advanced in Europe, but he also considers that the means mobilised – even within the recovery fund, supposed to devote at least 20 per cent of the cash to digitalisation – are simply not enough.

“I think the money we’ve put on the table so far has been peanuts, where I think we should be spending massively is bio-science. The COVID pandemic has shown that the Europeans are pretty good, bio-science, and that’s going to be the way of the future. It’s not about governments, it’s about research and private companies. We need to move ahead on AI, and we need to spend a lot of money on R&D but forget building new semiconductor factories.”

The semiconductor industry is definitely a long-term game; the question is whether the EU has opted for the right tactics to play it.

Article by Beatriz Ríos, Euranet Plus News Agency